A Homily Delivered 7 December 2014 for the Second Sunday of Advent (Year B)

December 7, 1941, “a day that will live in infamy,” a day that marks our country’s entry into World War II due to the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese. Today, seventy-three years later, I’d like to give you four brief vignettes, or snapshots as it were, of events that took place during and shortly after the Second World War. I believe that, of all the priests in our diocese, I can do this with impunity because of my Japanese ancestry.

Many people don’t know that both my father’s parents came from Japan and settled in California, making yours truly half Japanese. By the way, on December 8, 1941, my father, who was in his junior year at Hahnemann Medical School in Philadelphia, tried to enlist in America’s armed forces. My Uncle Toshikatzu (“Uncle T” for short) was accepted into the navy. Dad, however, was turned down and, unable to return to California, remained on the East Coast where, incidentally, he eventually met my mother. (Consequently I am, in all truth, a byproduct of World War II.) The rest of Dad’s family spent three and a half years in the internment camp at Poston, Arizona. Thus what I say here is in no way intended to be disparaging of the Japanese, or of anyone, for that matter.

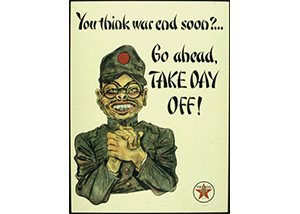

Here’s Vignette #1. In 1942, the Texaco Oil Company produced a propaganda poster featuring a grinning Japanese soldier and a slogan in large, oriental-type letters that read: “You think war end soon?… Go ahead, TAKE DAY OFF!”

Texaco’s message was clear: If Americans slacked off from the war effort for reasons of personal comfort, they could be giving the enemy the winning advantage.

Vignette #2: Msgr. Joseph P. Dooley, a priest of our diocese ordained in 1956, fought in the Second World War and was actually left for dead on the beaches of Normandy. He tells how, at one point during the war, his unit routed a band of German soldiers who had been occupying a strategic French village. All the Germans managed to escape—all, that is, except for six. Why were these German soldiers taken? Because, rather than remain on duty with their own soldiers, they chose instead to allow themselves to be entertained by French women. Again, the message is obvious: If you are in the wrong place at the wrong time and doing the wrong thing, you’re liable to get caught.

Vignette #3: American Admiral Bill (or “Bull”) Halsey was more than outspoken in his utter detestation of the Japanese. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, he asserted, “Before we’re through with them, the Japanese language will be spoken only in hell.” On another occasion he said: “People ask me if there is such a thing as a good Jap. I say YES, provided he’s been dead for six months.”

In October 1944, the U.S. Seventh Fleet under Admiral Thomas Kinkaid launched an invasion force on the island of Leyte in the Philippines. Halsey’s Third Fleet was assigned to guard the San Bernardino Straits, thus providing cover for the Seventh Fleet’s operations. The Japanese, knowing full well how much Halsey despised them, sent their Admiral Ozawa and his ships down from the north as a decoy to lure Halsey away from the straits. The trick worked. Halsey, without informing either Admiral Kinkaid or Admiral Nimitz of his intentions, took the bait and steamed after Ozawa, leaving the Seventh Fleet vulnerable. Some have called this “Halsey’s blunder.” Before long, the Seventh Fleet found itself under fierce attack from Japan’s Center Fleet. The battle for Leyte Gulf proved to be one of the most horrendous in the Pacific. The obvious conclusion is that it would have been better had Halsey not followed his passions but stayed where he was assigned.

Vignette #4: Shortly after World War II, my friend Lehmon Mixon was serving aboard the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Leyte (named after the island mentioned above). A sudden fire broke out aboard ship. Many of the sailors ran to where they thought they would be safe. Mixon, however, stood by his post. Ironically, there was an explosion in the very place to which the seamen had fled for refuge. They were killed; Lehmon survived to tell the story. From that day on, he made it his policy never to abandon his post.

Here it is, crew. The struggle to be a good Catholic, the battle to preserve one’s soul for eternity, is, without a doubt, the greatest war we will ever fight. Saint Paul says (Ephesians 6:12): “For our wrestling is not against flesh and blood, but against the Principalities and the Powers, against the world-rulers of this darkness, against the spiritual forces of wickedness on high.” In our second reading at Mass today, Saint Peter asks, “…what sort of persons ought you to be”? He says we should conduct ourselves “in holiness and devotion, waiting for and hastening the coming of the day of God” (2 Peter 3:11-12). In other words, in this spiritual warfare, we must stand by our post. We must stand by our post despite the temptation to slack off. Remember the Texaco poster. We must stand by our post despite our passions. Remember the six Germans captured by the Americans. We must stand by our post despite even our hatreds. Remember Admiral Halsey in the Leyte Gulf. We must stand by our post even when our own safety is threatened. Remember Lehmon Mixon aboard the Leyte.

Jesus urges us to hold fast to the truth come hell or high water, to keep our commitments, to defend the Faith—not only for ourselves but for those whom we love. We must, at all costs, stand by our post.

God bless you. Arigatou gozaimasu.