July 1999

The babble of some people is like sword thrusts,

but the tongue of the wise is healing.

–Proverbs 12:18–

Introduction

I always felt a secret twinge of regret that my poor eyesight prevented me from following in my surgeon father’s footsteps. But after teaching at Bethlehem Catholic High School for the last ten years, my eyes have been opened. Disciplining (or making disciples of) young people is not all that different from treating patients. The human tongue, after all, can sometimes prove to be the keenest of scalpels. In the article that follows, I discuss six lessons I learned from my father and how they can be applied in the realm of education.

Dad

Six Simple Rules

This past week, I discovered that, on two separate occasions, I had used words that, in one instance, caused great joy, and, in the other instance, caused a great deal of pain. Ironically, in neither case did I even begin to suspect that the words I used would have the effects that they did. Having a tongue entails an awesome responsibility. Human speech is powerful indeed.

In Isaiah 55:10-11, we read:

Yet just as from the heavens the rain and snow come down and do not return there till they have watered the earth, making it fertile and fruitful, giving seed to the one who sows and bread to the one who eats, so shall my word be that goes forth from my mouth; It shall not return to me empty, but shall do what pleases me, achieving the end for which I sent it.

This passage clearly deals with the efficacy of the word of God. Just as the heavens send down rain and snow upon the earth, and these have their effects, so the word of God, when it is sent forth, is never without its effects. When God speaks, things begin to happen. (See Genesis 1 and Hebrews 4:12.)

Because we human beings are made in the image and likeness of God (Genesis 1:27), our words are powerful also sometimes for good and (unfortunately) sometimes for ill. This truth has grave implications for all of us but especially for parents and those who teach young people. The souls of the young are impressionable. What we say around kids will have an impact. They might give us blank stares, but their minds are recording everything they hear.

To this day, I can still remember many of the words my own father used with me. Dad died in 1985, but I can hear words he spoke to me echoing in my head just as if he had uttered them only yesterday. As many of you know, my father was a physician. For almost forty years, he worked as a general surgeon on the staff of Sacred Heart Hospital in Allentown, Pennsylvania. I am always delighted when his former patients come up to me and tell me what a good man he was. Such individuals are, as it were, living relics of someone I love deeply. God gave me two wonderful parents, but this essay is dedicated to my father. Mom, someday I’ll write about you too!

Now when it came to using a scalpel, Dad had three simple rules which he followed religiously.

Rule #1: If you must use a scalpel, always work under aseptic (i.e. sterile) conditions.

Rule #2: If you must use a scalpel, do so with a steady hand and never under the influence of anger.

Rule #3: If you must use a scalpel, sew up the incision with small stitches to prevent leaving a scar.

I believe that these three rules apply, not only to surgeons, but also to parents and to those of us who interact with young people. We whose task it is to guide the young inevitably find ourselves in the role of disciplinarian. When we use the knife blade of our tongue in discipline, we must exercise the same kind of care that a skilled surgeon does in handling a scalpel. Let’s then take a closer look at Dad’s three rules.

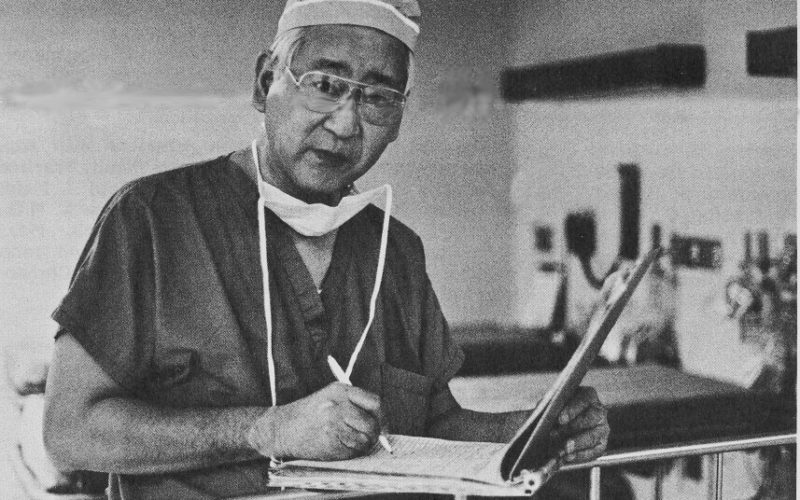

Young Toshio as an intern at Sacred Heart Hospital

Rule #1: If we must use the scalpel of our tongue in discipline, we must always work under aseptic conditions. In other words, we ought never to use profanity, sarcasm, put-downs, or abusive language. (See Matthew 5:22.) If a surgeon’s knife is unsterile, there is a strong likelihood that the incision, even after it is sewn up, will become infected. So too, if our tongues, the scalpels of our discipline, are contaminated with profanity, sarcasm, put-downs, or abusive language, it is very likely that the incisions they make in the souls of the young will become infected with anger and hostility. How sad! For the wounds of the soul are even harder to heal than those of the body.

I can honestly say that, while growing up, I never heard my father use profanity or abusive language with either his wife or his six children. Sure, Dad scolded us kids from time to time. Of course he raised his voice. Of course he laid down the law. His purpose in doing so, however, was always to heal and to promote growth, never to inflict pain for its own sake.

When I was first assigned to teach high school sophomores, I was utterly amazed at just how messy a classroom could become. Anything that could possibly find its way onto the floor did, and from there it made its way into my dustpan. As a matter of fact, sweeping the floor at three o’clock each afternoon was for me somewhat of a rewarding experience. A clean classroom and a full dustpan seemed to be the only tangible results of all that I had accomplished on any given day. Not surprisingly, I began referring to my young charges as kinderschweine (a German word meaning “child pigs”). “It’s only a term of endearment,” I protested when a friend questioned my linguistic creativity. On reflection, however, I came to realize there was indeed a note of sardonic humor in my supposed affection. I therefore promised God that I would never again call my sophomores pigs. Today I make a habit of attaching the Japanese suffix-san (meaning “honorable”) to the name of each of my students. Surely it’s not my imagination that my classroom is less of a mess at the end of the school day. Surely I am not dreaming when I observe that each year my sophomores are acting more and more like human beings. Could it be that people live up to the expectations placed on them by others?

Rule #2: If we must use the scalpel of our tongue in discipline, we should avoid making an incision under the influence of anger. To put it another way, we need to become aware of, own, and then process any unresolved anger within ourselves if we are to become better disciplinarians. We will be able to act as good guides and role models for the young to the extent that our own past wounds are healed. Otherwise we will find ourselves dumping out our own anger all over the kids, and who knows what harm we will end up doing? A scalpel used in anger is no instrument of healing.

As a new teacher, often I was quite angry with my students. But I have discovered that this anger was not the result of anything which they had done; it was instead rooted in me. I was angry over the fact of my limited eyesight, and I unknowingly took my anger out on my kids. If, for example, I caught a student chewing gum, I immediately assumed that he was doing so only because I happened to be blind and he wanted to take advantage of me. Sounds ridiculous, doesn’t it, but I am gradually learning from my pupils. I now realize (Hooray!) that kids chew gum for many reasons, only rarely for one that is motivated by my lack of vision. Processing anger is easier said than done, and I could write an entire essay on this one subject. The point is this. Only as I begin to work through the past issues of my own anger will I be competent in administering discipline to my students.

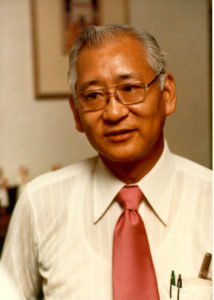

Dad and Me

Rule #3: If we must use the scalpel of our tongue in discipline, we must sew up the incision with small stitches to prevent leaving a scar. In disciplining the young, it is vital that we tie up any loose ends. More specifically, every act of discipline should be brought to definitive closure so that the child knows beyond a shadow of a doubt that we bear him no grudge. The best way for us to do this is to spend time with the young person outside the disciplinary setting in contexts of joy and praise. Thus we make it clear to the child that “that was then, and this is now.” The child will perceive that we harbor no ill feelings, and he in turn will cherish no lingering hostility. Conversely, the parent or instructor who speaks to a young person only in discipline and never in contexts of joy or praise does not tie up loose ends. The scars of such discipline will be large and ugly, sometimes leaving the soul of the child disfigured for life. In all matters of correction, careful closure is absolutely necessary.

As a surgeon, Dr. Toshio Ezaki was known for his expert stitching. As a father, he knew how to balance discipline with joy and praise. I can remember countless joyful times spent with my father. When I was a small child, I used to love “wrestling” with Dad or else just curling up quietly in his lap. In addition, happy recollections of my family’s annual August vacations, of my first time fishing, and even of my first experience with a straightedge razor remain vividly fixed in my mind. Above all, I will always cherish the memory of that Saturday afternoon when Dad and I went to the pet shop all by ourselves to purchase my first aquarium. That wonderful afternoon was positively delicious.

My father was also generous in giving praise to his children. He had a well-known habit of bragging about his progeny to every prospective patient who came into his office. But he often took occasion to compliment us directly. I distinctly recall Dad telling me that I was brilliant and that I would play a key role in our family’s well-being. He even used to call me “Ichiban,” which is the Japanese word for “Number One Son.” Now to be quite honest, I would like to think of myself as brilliant, but I am not at all convinced that I am. Nor am I sure that I will have a great impact on my family’s future. Also, I now know that ichiban is really a designation of birth order and not a title of favoritism. What is important, however, is that Dad thought I was brilliant. He had faith that I would influence our family for the better. He gave me a nickname that none of his other children possessed. I wanted (and still want) with all my heart to live up to his lofty opinions of me. My father definitely knew how to make his stitches small.

If, in the course of the school day, I have occasion to reprimand one of my students, I make it a point the following day to praise the person in some way, or even to joke with him. I want the student to know that there are no hard feelings. There may indeed be consequences to the student’s inappropriate behavior, but I want to make it clear that I am not holding a grudge. In the past, letting problems roll off my back was not one of my strong points, but today I begin to see the wisdom in a maxim handed on to me by a veteran teacher: “Every child is entitled to a clean shirt and a fresh start each day.”

I have been teaching high school sophomores for the past ten years, but only recently have I begun to recognize the real value in being present at my students’ extracurricular activities. Last year, for example, I made an appearance for the first time at some of our football team’s practices and games. This was no easy matter for me. I know next to nothing about sports, and I also need someone to accompany me and explain exactly what is happening on the field (my own private sportscaster, as it were). But the results of my tentative ventures into the realm of football were both immediate and dramatic, even almost miraculous. Junior and senior football players began greeting me in the halls. Sophomore football players began to participate more in class. I also got frequent requests from my students to attend their various sporting events. I even received some very positive feedback from parents. Best of all, the whole atmosphere of my classroom became more relaxed. I have thus come to the conclusion that “tying up loose ends” may do more than simply bring closure to discipline. It may actually serve to reduce the necessity of future disciplinary action. There is real truth in the familiar saying: “Kids don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.”

Up to this point, I have discussed my father’s rules for handling the scalpel, but what about his procedures both before and after the surgery itself? Here again, the rules Dad followed were three.

Rule #4: Value the patient; treat the pathology.

Rule #5: Give the patient clear indications how the pathology is to be treated.

Rule #6: Know when to use the scalpel and when to use salves.

These maxims, too, are instructive for all of us who undertake the task of disciplining the young. They are, perhaps, even more important than Rules #1, #2, and #3.

Rule #4: Value the patient; treat the pathology. In other words, when it comes to discipline, we must love the child but correct the behavior. In all that we do as disciplinarians, we must value the person and never make the individual feel as though he is a failure. The real problem is not the person, but rather the negative behavior. Any disciplinary action we take must be focused on the behavior. We must never target the individual.

“Whenever you visit the sick,” my father used to tell me, “try your best to get down to the person’s eye level, and, if possible, physically touch him in some way.” Another piece of advice was the following: “No matter how many people you have to see, treat each individual as if he were the only person in the world.” Clearly, my father valued people. I am reminded of numerous confirmations of his person-first philosophy from the lips of his former patients. Even today they say things like this: “Sometimes I would sit for hours in your father’s waiting room, but I never really minded having to watch TV or chat with other patients. There was a certain comradeship in that outer office. None of us was in any hurry. We all knew that, once we got in to see the doctor, he would prop his feet up on his desk, take out a cigar, and act as if no other person mattered but the one sitting before him.” Yes, Dad did run his office like a clinic on a first-come-first-served basis, no appointment necessary. No, I am not suggesting that all physicians do the same. What I am saying is that every one of us could take a lesson from my father. The person is primary. Compassion is key.

Yet my father was quite decisive and sometimes even downright aggressive in combating disease. In cases of breast cancer, for instance, he did not hesitate to recommend a radical mastectomy (lymph nodes and all) rather than taking even the slightest chance of a recurrence. When it came to imperative procedures, Dad pulled no punches. Here, I cannot help thinking about my Aunt Annamae. She phoned one day and announced that the toes of her left foot were turning black. As a self-prescribed remedy, she had been soaking the offending digits in vinegar. My father got into his car and drove thirty miles to examine her. A vinegar solution may, perhaps, check the spread of athlete’s foot, but nothing short of amputation can halt the ravages of gangrene. “Bibs, it’s your leg or your life,” Dad bluntly observed. My aunt, naturally enough, was all but devastated, yet even in her anguish, she knew that her doctor was on her side. She was not the enemy. The gangrene was the menace. People aren’t problems. Pathologies are.

My father never regarded any of his children as problems. In spite of my blindness, which must have caused him no little heartache, he in no way made me feel the least bit deficient as a human being. Looking back over my childhood, it seems to me that a great many things around the house got broken all because of me. Clocks, toys, a statue, a music box, and even my own clarinet met their demise either through my lack of eyesight or through my childish carelessness, yet it was not in Dad’s nature to belittle me or anyone else, for that matter. I still recall the words he said to me after I accidentally broke my clarinet. I was quite upset over the mishap and retreated to my room to worry about the ruined instrument. What would Dad do when he found out? That night, when my father got home from the office and was told of my misery, he came to my bedside and spoke gentle words of reassurance: “Don’t worry, Bernard. It’s only a material thing. Things can be replaced. People are more important than things.”

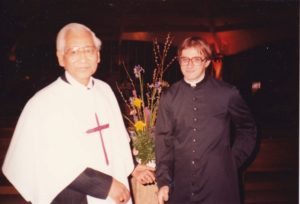

Dad at His Baptism by Fr. Stephen Radocha – 2 April 1983

The irreplaceable uniqueness of the human person! Would that I had remembered this in my early days of teaching! The incident I am about to relate is one of which I am very much ashamed. I wish I could excuse myself, at least partially, on the grounds that I acted on impulse, but what I did was totally premeditated.

In the fall of 1989, I had a boy in my seventh period whose name I won’t mention here, even though it is forever etched in my memory. One afternoon, I chanced to see this young man throwing a wad of paper across the room. My gut reaction was immediate. “How dare this brat take unfair advantage of my blindness!” I thought to myself. “I’ll fix his wagon!” I perceived the young man’s offense as a personal affront, and I was going to get even. That night I plotted how I would make him pay for his blatant disrespect. The next day, in front of his peers, I thoroughly humiliated the boy by forcing him to sweep the floor after I had angrily dumped out the contents of the trash can. I did this, not once, but three times! I wanted to teach that kid a lesson he wouldn’t forget. I apparently succeeded. Sure enough, the lad was cowed into submission for the next several days. All seemed well. Weeks later, however, long after I had forgotten the unfortunate episode, I found myself reading one of the culprit’s essays. At the very bottom of the last page were written four words in the smallest of print: I am a failure. I was stunned. It was I who had failed—all because I had allowed my own unresolved anger to get the best of me. I had failed to draw the vital distinction between the person and the behavior. I had dealt a crushing blow to a teenager’s self-worth. I had acted more like a beast than a priest. I had become, as it were, an instrument, not of God, but of the devil. I was more blind than I knew. Good Lord, forgive me! As for my former student, I am still praying for a happy ending.

Rule #5: Give the patient clear indications how the pathology is to be treated. Saint Augustine (d. 430), the great convert to Christianity, defined the process of conversion, not only as the turning away from sin (conversio a peccato), but also as the turning toward God (conversio ad Deum). We who are concerned with disciplining the young might render the saint’s definition in more everyday language: “You can’t take something away from a child without replacing it with something better.” To put it another way, discipline is not just saying NO. It also involves affirming a greater YES. The parent or teacher who merely gives negative criticism without offering constructive advice is not doing his job. The same can be said for the disciplinarian who resorts to “the silent treatment.” Both tactics can cause real damage in the souls of the young. Effective discipline means communicating a new and better vision. This vision, in turn, must be translated into corrective action.

As a physician, Dr. Toshio Ezaki was always clear in imparting his vision regarding treatment and recovery. Prior to surgery, he would often be found at the bedside of a patient, pen in hand, skillfully sketching diagrams of the upcoming operation. Once the surgical procedure was completed, my father would give specific guidelines relating to the recovery: a regime of exercises and diet, expectations about time of convalescence, etc. No patient of Dad’s ever went away uninformed or unenlightened.

My father was also a particular favorite among student nurses. Unlike some surgeons, he was never arrogant or impatient with those in training. Even under the intense pressure of the operating room, he never lost his cool if a scrub nurse mistakenly handed him the wrong instrument. On the contrary, he would go out of his way gently to point out the error and give encouragement. Student nurses always felt at ease when assigned to assist my father in the OR. So beloved was he by them that in 1980 he was given the honor of addressing the very last graduating class of Sacred Heart School of Nursing (Allentown, PA). I myself was present for the occasion along with my mother and other members of our family. The feeling of love and admiration in the air was almost palpable.

At home, Dad was always the most patient of teachers. Whether instructing my mother on the fine art of preparing sukiyaki, giving my sister Marybeth her first driving lessons, or helping my sister Elizabeth with her science projects, he was somehow able to communicate a vision of the job well done. But what about me? How exactly did my father enable me to glimpse the Good that he perceived? He did this, I think, by telling stories. Without a doubt, Dad was a consummate story teller. I loved listening to his accounts of his early life – his boyhood on a California farm, his uncertain search for a job after the outbreak of World War II, his days as an army captain in the France of the 1950’s. Every story had its lesson. Even a farm boy who spoke only Japanese could succeed in America. Adversity brings out both the best and the worst in people. Raising a family on foreign soil and under difficult conditions is no impossibility, provided there is love. Just as my father drew pictures for his patients with the help of a trusty ball-point pen, so he painted images for his son with the power of well-chosen words. Today, whenever I teach or preach, I try to follow Dad’s good example. I tell stories, use anecdotes, describe situations in detail—anything to get the point across. In other words, I try to speak in pictures. That is how my father shared his visions with me. The essay you are now reading is, in a way, a tribute to Dad’s remarkable gift of teaching through images. At the same time, it is my own modest attempt to follow in his footsteps.

For the past nine years, I have decorated my classroom as if it were a ship. Lanterns, a ship’s wheel, a sail, bells, and even an anchor all contribute to the nautical motif. In this way, I hope to maintain discipline and at the same time capture my students’ imaginations. Below is an excerpt from page 1 of my Ship’s Rules. The picture I am trying to create is one of adventure and joy:

The Importance of Being in Your Rowing Station on Time

It is difficult for me to deal with a lot of crew members milling around aimlessly aboard ship. For this reason, the Captain hereby institutes the following policies.

Immediately after the bell signals the beginning of class, I shall pipe you aboard with my boatswain’s whistle. By the time I finish piping, you must all be seated in your assigned rowing stations. Any crew member not in his or her rowing station at this time automatically becomes a stowaway.

First-class stowaways are those crew members who have not made it aboard ship by the time I finish piping. They must stand at the gangplank, salute, and request permission to come aboard. Their penalty is the requisite number of demerits for lateness to class.

Second-class stowaways are those crew members who, although on board ship, are not yet seated by the time I finish piping. They too must stand at the gangplank, salute, and request permission to come aboard. Their penalty is a 30-minute, after-school, personal detention to be served the following school day. During this time in detention, second-class stowaways will swab the deck (sweep the floor), scrape barnacles (remove gum wads), or perform other tasks deemed appropriate by the Captain.

Remember: BE IN YOUR ASSIGNED ROWING STATION BY THE TIME I FINISH PIPING THE CREW ABOARD.

Again and again my sophomores tell me how much they appreciate my nautical theme. For me, it’s a way of making discipline fun. I think my father would be proud.

Rule #6: Know when to use the scalpel and when to use salves. My father, it seemed, had a salve for just about everything. As a boy, I can remember seeing jars and containers of all sorts of ointments. But even as there are salves for the body, salves whose purpose it is to promote healing, so also there are salves for the soul. Both are important. Neither should be neglected. Now when it comes to disciplining the young, I would like to recommend two very potent soul ointments. The first is humor. The second is the sincere apology.

Any nurse who knew my father will tell you that he was noted for his operating room humor. The jokes and anecdotes he told while in surgery served to release tension and soothe frayed nerves. The benefits of laughter can be enormous. In Proverbs 15:13, we read:

A glad heart lights up the face,

but an anguished heart breaks the spirit.

Then there is Proverbs 17:22:

A joyful heart is the health of the body,

but a depressed spirit dries up the bones.

As a teacher, I tell my students at least one joke every day, because I have found that a little humor goes a long way in fostering classroom harmony. I learned this valuable lesson from a young man named Jason.

It was seventh period in the spring of my second year of teaching. I looked around my room and soon discovered that my wonderful darlings had literally peppered the walls and pictures with spitballs and gummy worms. Even the Pope’s portrait had not escaped the volleys. That year, I happened to have a rather large poster of Our Lady of Guadalupe displayed prominently next to my desk, yet I noticed that none of the projectiles had come anywhere near the sacred image. The Virgin remained untouched by either wads or worms. “At least you urchins had enough decency to leave Mary alone,” I commented with no little irritation. It was then that Jason piped up in a tone of unabashed horror: “Father, we would never hit our Lady!” His obvious sincerity caught me off guard, and I did the only thing possible at that moment: I began to laugh. My own laughter, in turn, brought with it a sudden decrease in classroom tension. From then on, that particular class gave me no more trouble with spitballs, and never again did I see another gummy worm. At times, laughter is indeed the best medicine. A well-timed laugh can defuse a potentially explosive situation. It can transform a scowl into a smile.

Not all laughter, however, is appropriate. Jokes at someone else’s expense are bad enough on the lips of children, but when adults resort to such “humor,” the consequences can be quite serious. No one should ever be made the target of ridicule, especially in the context of discipline. Disciplinarians who habitually make use of mockery are more like butchers than surgeons. They forget that young people are not means to an end but rather are ends in and of themselves.

Is there a difference between ridicule and good-natured teasing? Indeed there is! Light-hearted teasing seeks gently to instill in others the precious gift of not taking oneself too seriously. It is always supremely sensitive to the feelings of others and knows when to back off. It is a sign of true affection. Ridicule, on the other hand, has no constructive purpose whatsoever. It strives only to make a jest of someone else’s apparent weakness. It is a coward’s road to laughter.

Alas! None of us is perfect. We all make mistakes. From time to time, we are all guilty of a kind of disciplinary malpractice. We say or do things we later regret. What, then, are we to do? The answer should be obvious. We need to say: “I’m sorry. It’s my fault. Please forgive me. What can I do to make it right?”

I have had to apologize to my students on several occasions. One Friday morning, for example, I thoughtlessly made a joke about a particular young lady’s braces. As the class burst into laughter, the girl in question put her head down on her desk, apparently embarrassed by the unwelcome attention. Over the following weekend, I did some soul searching and came to the realization that I owed my student an apology. Since my offense had been public, my apology would likewise have to be public. The end result was that my sophomores got to see their teacher admit he had been wrong. Not a bad lesson when you come to think of it! Perhaps in the future, those young people will be more willing to face up to their own shortcomings. No one is more shallow than a person who refuses to say, “I’m sorry.”

There’s an old saying: We teach what we most need to learn. As a priest, I often feel as though I preach what I most need to live. Thus I write this essay with the idea of clarifying for myself my own philosophy of discipline and of how young people ought to be treated. Yet I am also convinced that my father’s surgical wisdom can be applied by all who have the task of instructing the young: parents, teachers, youth group leaders, and even coaches.

Here I make special mention of coaches, because it seems to me that our society in general regards athletics as the great exception. Disciplinary practices which are not tolerated outside of sports are deemed perfectly acceptable when it comes to coaching. I am not at all sure why this double standard exists. Helmet and padding may indeed shield the young athlete’s body, but do we believe that protective gear somehow insulates the soul? Unless I am gravely mistaken, the demands of discipline are the same all across the board. I say this, not from the perspective of an ivory-tower critic, but from a conviction born of personal experience. I happen to know coaches who go out of their way to avoid profanity and put-downs, who spend quality time with their players off the field, who inspire young athletes with a vision of the Good, who, to put it briefly, remind me of my father. A good coach is worth his weight in gold.

Summary

God’s word is powerful and effective. It never goes forth without producing results. Because we human beings are made in the image and likeness of God, our words are powerful also. They never escape our lips without producing some effect—either for good or for evil. Those of us who work with young people (parents, teachers, coaches, and others) need to exercise particular care when acting as disciplinarians. We would do well to remember six rules of discipline that correspond to my father’s six rules of surgery:

Rule #1: Speak under aseptic conditions, i.e. without profanity, sarcasm, put-downs, or abusive language.

Rule #2: Keep a cool head, and avoid acting under the influence of anger.

Rule #3: Bring closure to discipline by tying up loose ends, i.e. by spending time with young people in contexts of joy and praise.

Rule #4: Love the child but correct the behavior.

Rule #5: Impart a clear vision of the job well done.

Rule #6: Give good example through the use of appropriate humor and a willingness to admit mistakes.

Parents and those of us who teach young people need to heed the words of the Hippocratic Oath. When using the scalpel of our tongue in discipline, we should try our very best “never [to] do harm to anyone.” Better yet, let us take to heart Saint Paul’s advice in Ephesians 6:4:

And you, fathers, do not provoke your children to anger, but rear them in the discipline and admonition of the Lord.