It was the autumn of 1980. My friend Ann and I were walking to the Harvard Divinity School Library. As we made our way along the little path that wound its way among fragrant pine trees, we paused before an old-fashioned looking lamppost, one of many on campus.

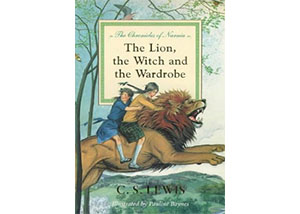

“That lamppost with the trees around it always makes me think of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,” observed my companion. Sure enough, the scene was indeed reminiscent of C. S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia. It was at the Narnian lamppost, so out of place in the middle of an enchanted wood, that little Lucy first met the faun Mr. Tumnis.

Shortly thereafter, I returned alone to the path outside the library. When I thought no one was looking (and one who is legally blind can never be entirely sure), I drew from my pocket a bumper sticker I had received from one of my college professors. This I surreptitiously affixed to the aforesaid lamppost. The bumper sticker read: THERE’S NO PLACE LIKE NARNIA. Strangely enough, the University never removed the sign.

A year and a half elapsed. I found myself sitting on the steps of old Divinity Hall with a few of my fellow students. We were discussing our reasons as to why we had decided to come to Harvard Divinity School in the first place. “What really clinched it for me,” declared a first-year M.Div. candidate, “was the lamppost outside the library with the words THERE’S NO PLACE LIKE NARNIA. I knew then and there that H.D.S. was the place for me!”

I was speechless. How could one small action of mine have such a profound impact on someone else’s life? What had started out as a little joke turned out to have rather serious consequences. Forgive me, Father, I prayed silently. I knew not what I did! Even the most seemingly insignificant acts can lead to surprising results.

Ironically, precisely the same point is made in the 2005 Disney film The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. When traitorous Edmund first arrives at the castle of the White Witch, he finds himself in a courtyard filled with snow-covered stone statues. On one of these statues, that of a lion, he traces the outlines of a mustache and glasses. At the end of the movie, as a redeemed Edmund and his siblings are being crowned Kings and Queens of Narnia, we get a glimpse of the same lion, now restored to life. The happy creature, proudly sporting the marks of glasses and mustache, still bears the imprints of Edmund’s handiwork.

Actions often have unexpected and long-lasting consequences. Our interactions with one another are not so much casual as causal. Here is another illustration—the best one of all:

In 1990, two years after my ordination, I received an amazing phone call. The person on the line identified himself as Mohammed, whom I remembered as having been an Iranian science major when we both attended Moravian College more than ten years earlier.

“Bernie,” announced Mohammed, “I want you to know that I have changed my name to Micah and that I have become a Christian—because of you!”

“What?” I gasped. “You’ve got to be kidding. What did I ever do to make you become a Christian?”

Mohammed, I mean Micah, went on to remind me of how, in college, I would sometimes help him “proofread” his term papers. Although he had an excellent command of spoken English, his writing sometimes needed a bit of polishing. On a number of occasions, Mohammed would read me his papers, and I would make simple suggestions for improvement. I might, for example, recommend that he substitute the word “difficult” for “hard.”

I had completely forgotten about these language-tweaking sessions. I was shocked to think that so small a kindness would be enough to prompt Mohammed to give Christianity a closer look. When I hung up the phone, I remember thinking that I had just experienced a foretaste of heaven. Surely one of the greatest joys of paradise will be the thought of having helped others get there! Surely one of the deepest regrets of hell will be the realization of having led others astray!

In his well-known address The Weight of Glory, C.S. Lewis marveled at our capacity for shaping the eternal destinies of our fellow human beings. He asserted:

“It may be possible for each to think too much of his own potential glory hereafter; it is hardly possible for him to think too often or too deeply about that of his neighbour…. It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you can talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics…. And our charity must be a real and costly love, with deep feeling for the sins in spite of which we love the sinner—no mere tolerance, or indulgence which parodies love…”

Let us, then, be careful of how we behave toward one another. We tread, as it were, on holy ground. We hold in our hands, in our speech, and in our actions the weal and woe of countless souls. It is not simply a matter of we ourselves getting to heaven. We must also think of the salvation of others. There is more in question here than the choice of a graduate school. What is at stake is nothing less than the Beatific Vision, heaven itself—both for ourselves and for our neighbor!